This page last modified 2003 Aug 04

Barlow Lenses

What is a Barlow Lens?

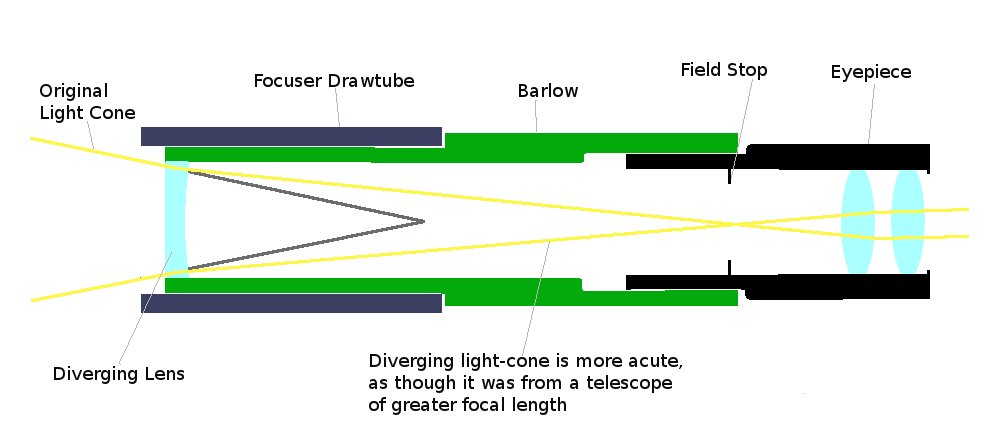

A Barlow is a negative (diverging) lens that is placed between the objective lens (or primary mirror — from now on these words will be used interchangeably) and the eyepiece of a telescope. It increases the effective focal length of an objective lens, thereby increasing the magnification. The idea is that 2 eyepieces and a Barlow will give you the flexibility of magnification of 4 eyepieces, and will give higher magnifications with less powerful eyepieces.

What are its Advantages and Disadvantages?

Assuming that the Barlow is a good one, the only disadvantage is a slight loss of light throughput — this is of the order of 3%. The advantages are numerous:

- Higher magnifications can be attained with longer focal-length eyepieces than would be possible without the Barlow. Short focal length eyepieces necessarily have optical surfaces that are more curved and therefore are likely to introduce more aberrations.

- A Barlow increases the effective focal ratio of the objective. This gives a

more acute light cone, which is less demanding of eyepiece quality because:

- Rays at the periphery of the cone are closer to being paraxial and thus are less subject to aberration.

- A smaller area of the field lens is used.

- Many eyepieces have an eye relief (distance of exit pupil from eye lens) that is directly related to its focal length. For example, the eye relief of a Plössl is 0.73 × its focal length. Thus, with these eyepieces, for a given magnification there will be greater eye relief with a barlow than without.

- Many eyepiece types do not work well with short focal-ratio objectives. The Barlow effectively increases the focal ratio, allowing the eyepiece to work well.

How does a Barlow work?

Barlow Amplification

The amplification factor of a Barlow is a function of its position in

relation to the eyepiece and the objective lens (or primary mirror). For any

given eyepiece and objective, the Barlow-eyepiece separation and the

Barlow-objective separation are related because the focal plane of the eyepiece

is the same as the focal plane of the objective-Barlow combination; as the

separation between the eyepiece and the Barlow increases, the separation of the

Barlow and objective decreases.

The amplification factor of a Barlow

can be increased by increasing its separation from the eyepiece using an

extension tube — it must simultaneously be brought closer to the objective.

One thing that you need to watch for with Barlows used outside their

design amplification factor is spherical aberration. SA will be minimised at the

design factor, but will almost certainly be present outside this, although it

may not be discernible. (But visually, using the old trick of shifting the

Barlow to the "other" side of the star diagonal or of using extension

tubes, this may be compensated by reduced SA in the eyepiece, as a

consequence of a more acute light cone.)

Eyepiece Choice

If you use a Barlow with fixed-focus eyepieces, you need to give some

thought to a suitable choice. If, for example, you have a x2 Barlow and a 25mm

eyepiece, there is little point in acquiring a 12.5mm; it will mimic the 25mm +

Barlow. A suitable choice might be 32mm, 18mm, 12mm.

Stop here unless you fancy some basic high school physics & maths.

Barlow Maths

Calculating Barlow magnification:

F = focal length of objective or primary

f = focal length of Barlow [1]

J = joint focal length (effective focal length)

d = separation of Barlow and original focal plane (objective focal

plane)

x = separation of barlow and new focal plane (eyepiece focal

plane)

M = amplification of Barlow

J = (F×f)/(f-d) ...(1) (combined lens formula)

M = J/F ...(2) (by definition)

=

f/(f-d)

The separation of the Barlow and the new focal plane can be calculated from

M and f:

x = f×(M-1) ...(3)

...from which we get :

M = 1 + (x/f)

One of the connotations of all this is that a Barlow that is its own

focal length inside the original focal plane (d) will produce a

collimated (i.e. parallel) beam. Another is that d only needs to

change slightly to bring about significant variations in x (play with

the formulae — or your telescope — to see this) [2].

Finding the approximate Focal Length of a X2 Barlow

The simplest way to do this is as follows:

- Locate the location of the field stop inside an eyepiece.

- Mark this position on the outside of the eyepiece barrel.

- Locate the position of the middle of the lens grouping in the Barlow.

- Mark this position on the outside of the Barlow barrel.

- Insert the eyepiece into the Barlow.

- Measure the distance between the two marks. This is the approximate focal length of the Barlow.

Note: This can only be approximate as the distance of the field stop from the "shoulder" of the eyepiece barrel varies from eyepiece to eyepiece. This is why the marked amplification factor of a Barlow can only be nominal.

Worked examples:

1. Based on Separation of Eyepiece Focal Plane and Barlow

Let us take a 75mm focal length x2 (nominal) Barlow used at its designed

amplification. (f = 75mm, M = 2)

M = 1 + (x/f)

δx = f(M - 1) = 75(2 - 1) mm = 75mm

This

relationship (the separation of Barlow and the new focal plane is equal to the

focal length of the Barlow) holds for any x2 Barlow.

Let us now

use the old trick of increasing Barlow amplification by inserting a star

diagonal between the eyepiece and Barlow. Assume that the star diagonal adds

80mm to the optical path.

M = 1 + (x/f) = 1 + (75 + 80)/75 = 3.07

i.e.

a nominal x2 Barlow has become an (approximate) x3 Barlow. Similarly, the

introduction of a 150mm extension tube instead of the diagonal will give an

amplification factor of x4.

2. Based on Separation of Objective Focal Plane and Barlow.

Let's take a 150mm f/10 objective (F = 1500mm) with a 75mm focal

length Barlow (f) placed 50mm inside focus (d).

Substituting

in equation (1):

J = (F×f)/(f-d)

= (1500 × 75)/(75-50) mm

= 4500mm

Substituting in equation (2):

M = J/F

= 4500/1500

= 3

Hence we have an amplification factor of ×3.

Substituting

in equation (3):

x = f×(M-1)

= 75 × (3 - 1) mm

= 150mm

Using the same objective with the Barlow 37.5mm inside the original

focus, equation (1) gives J = 3000, equation (2) gives M = ×2,

and equation (3) gives x = 75mm. [2]

[1] For the purposes of these equations, the focal length

of the Barlow is signed positive. Although I generally use RIP, in this context

I prefer this way of doing things because the introduction of a negative f

tends to lead to more errors. If you wish to use the RIP convention, f

is negative and the equations must be modified accordingly. I will leave that as

an exercise for the interested reader.

[2] Note, from the numerical examples, how a 12.5mm

shift in the Barlow has resulted in a 75mm change in x. This also

explains why, when you use a zoom eyepiece (zoom is essentially a moveable

Barlow), only slight refocusing is required when you change the effective focal

length of the eyepiece.