This page last modified 2001 August 25

The Tides

Questions about the tides arise regularly on astronomy newsgroups. This

document is an attempt to answer some of these questions.

What causes the tides?

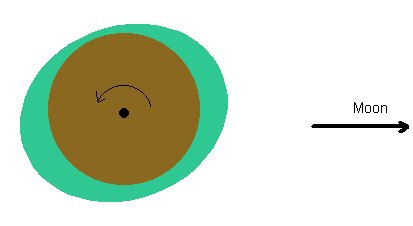

Our initial considerations about tides will consider a simple model in which we have a non-rotating Earth that, were it not for tides, would be covered with a uniform depth of water, which exerts no frictional drag. We will add complications like rotation and topography later. This is also a qualitative treatment in which none of the drawings is to scale!

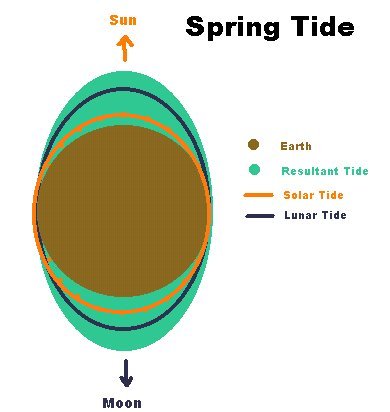

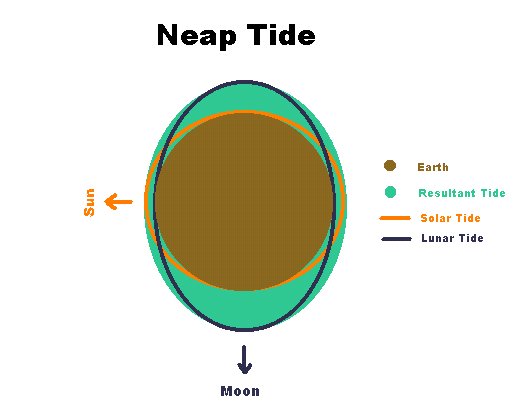

Tides arise as a consequence of the gravitational interaction of the Earth with the Sun and the Moon. That of the Moon is greater than that of the Sun. Most people are aware that at syzygy (when the gravity of the Sun and Moon act in the same line) there are Spring Tides.

and at quadrature (when the gravity of the Sun and Moon act perpendicularly

to each other) there are Neap Tides:

The Earth rotates beneath the water once per day, thus (in this simple

model) there are two high tides daily.

Also, note that the Moon orbits the

Earth in an elliptical orbit, as does the Earth orbit the Sun. At perigee and

perihelion the gravitational attraction of the Moon and Sun respectively will be

greatest, thus the resulting tides will be higher. The highest spring tides will

occur when the Earth is at or near perihelion and the New or Full Moon is at or

near perigee.

Why are there two tides a day?

This is a question that arises regularly, and is one to which many of the

answers given are either wrong or overly complicated. Before we embark on this

it is necessary to briefly consider frames of reference. Many of the

explanations given for the tidal bulge on the side of the Earth distant from the

Moon invoke an imaginary force called centrifugal force [1].

This is a mathematical construct that permits us to consider a rotational frame

of reference. It is unnecessary; the force that is responsible for raising tides

is the gravitational force. If we consider an inertial frame of reference

we can dispense with the concept of a centrifugal force and simplify things by

considering only real forces.

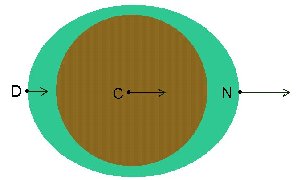

Imagine the Moon to the right of your

computer screen.

Let's take a line through the centre of the Earth and 3 points

on that line. D is the point on the Earth's ocean surface most distant from the

Moon, N is the point on Earth's ocean surface nearest the Moon, C is the Centre

of the Earth. N is nearest the Moon, so experiences the greater gravitational

pull, D is most distant, so it experiences the least pull, and C experiences a

pull intermediate between the two:

Let's take a line through the centre of the Earth and 3 points

on that line. D is the point on the Earth's ocean surface most distant from the

Moon, N is the point on Earth's ocean surface nearest the Moon, C is the Centre

of the Earth. N is nearest the Moon, so experiences the greater gravitational

pull, D is most distant, so it experiences the least pull, and C experiences a

pull intermediate between the two:

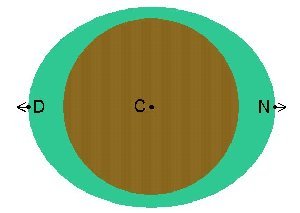

Assuming a rigid Earth [2] cloaked in fluid ocean, there

is a bulge at N because the water there is being pulled more than C and there is

a bulge at D because it is being pulled less than at C. If this doesn't satisfy

you, let's play with the vectors. The arrows on the diagram above are force

vectors. If we subtract the force vector at C from those at D and N, we have:

Hence, relative to the centre of the Earth, the force vectors at D and N are opposite and approximately equal [3], hence 2 tides.

Why isn't the high tide directly underneath the Moon?

There are two components to the answer to this question:

A) If we

desimplify our original model by considering the friction between the body of

the Earth and the sheath of water, we see that the Earth tries to drag the tidal

lumps around with it in its daily rotation, and the Moon tries to retard it. The

result of this is that the tidal bulge 'leads' the Moon [4].

A) If we

desimplify our original model by considering the friction between the body of

the Earth and the sheath of water, we see that the Earth tries to drag the tidal

lumps around with it in its daily rotation, and the Moon tries to retard it. The

result of this is that the tidal bulge 'leads' the Moon [4].

This is further complicated by the relative positions of the Sun and the Moon (see below) that result in variations of the tidal period.

B) If we further complicate our simple model by introducing real topography,

we find that this changes things dramatically. Real tides are also the

consequence of oscillations in the ocean basins, of funnelling into narrow

waterways, of retardation by shallow water, etc. Real tides cannot be predicted

from first principles and need empirical observation for at least a complete

Saros period (i.e. 223 synodic months, after which the Sun and Moon return to

the same positions in the sky) before reasonably reliable predictions can be

made, but even these will be affected by things like barometric pressure.

Why are alternate high tides higher than the intervening ones?

The short answer is that this is not necessarily the case. When it

does happen a frequent wrong answer that is given is that the tide on

the Moon side of the Earth is higher, and then resorts to a spurious argument

about gravitational attraction and centrifugal forces.

The short answer is that this is not necessarily the case. When it

does happen a frequent wrong answer that is given is that the tide on

the Moon side of the Earth is higher, and then resorts to a spurious argument

about gravitational attraction and centrifugal forces.

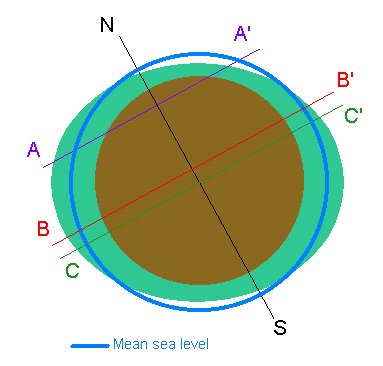

The correct

answer is that it is due to the fact of the 23.5° orbital tilt of the

Earth's axis of rotation with respect to the plane of the ecliptic (aka the obliquity

of the ecliptic). The moon's position remains within 5 degrees of the

ecliptic. The resulting gross tidal bulges with respect to mean sea level look

like this:

The first thing to note is that at the latitude A, there is only one high

tide per day, because at A' the water opposite the tidal bulge at A is actually

below mean sea level. This is called a diurnal tide.

At

latitude B, the tidal bulges are different heights above mean sea level, with

the tide being higher at a point when it is rotating under B than it is under

B'. This is called a mixed tide.

At latitude C the tidal bulge is

the same height above mean sea level at both C and C'. The tides will therefore

be of approximately the same height. This is a semidiurnal tide.

The difference in height of alternate tides is called 'diurnal

inequality' and is dependent on the declination of the Moon. When the Moon

is south of the (celestial) equator, 'Moon-side' tides in the N hemisphere will

be lower than the other tide; they will be higher when the Moon is N of the

equator.

Why is there so much variation in the tidal period?

There are several reasons for this:

The explanation given above for how the tide

'leads' the Moon is grossly simplified, in that it does not take account of the

Sun. During waxing crescent and waning gibbous phases of the Moon the geometry

is such that the 'lead' is greater – this is called tidal priming.

During the waxing gibbous and waning crescent phases the 'lead' is reduced –

this is called tidal lagging.

Because of the ellipticity and

obliquity of the Moon's orbit, the period between its meridian passage (aka.

culmination, transit) varies, thus varying the length of the tidal day

whose mean is 24h 50min.

The motion of the Moon is (un)reasonably

complicated. Not only does it move in an ellipse whose plane is inclined to that

of the ecliptic, but this orbit is perturbed by the Sun. The changing effect of

the Sun's gravity is called variation. To it must be added

evection and annual inequality. Evection is a change in

the eccentricity of the orbit. Annual inequality is the effect of the

Earth not maintaining a constant distance from the Sun owing to its elliptical

orbit. These perturbations affect the mean anomaly (the angle of an

imaginary mean moon, travelling at constant angular speed in a circular

orbit, from its perigee, measured at the centre of the circle) of the Moon by up

to about 10°. The true anomaly (angle of true Moon, real orbit,

etc.) is a function of the mean anomaly and the eccentricity.

[1] To those who wish to insist that we must consider a rotational frame of reference because we are living in one, I have two things to say:

- Consider the words of Mike Humberston written in the newsgroup

uk.sci.astronomy:

"This is a bit like a person who lives inside a box claiming that the limits of the universe are the edges of his box. Those of us who choose to live outside of boxes can see that he is incorrect." - Get your information about tides here. As you will see, the force diagrams become more complicated in a rotating frame of reference.

[2] In fact the Earth is not rigid. It has approximately the same rigidity as mild steel and the crust experiences tides of the order of a few centimetres in amplitude. We do not notice these because we do not have a point of reference against which to experience them.

[3] The force at N is slightly higher than the force at D, owing to the inverse cube relationship between separation and tidal force. However, this is not the cause of the tidal inequality. There is also a comparatively minuscule tide-raising force resulting from the centripetal acceleration that is due to the Moon and Earth 'orbiting' their barycentre (which is 1600 km deep inside the Earth) with a period of one sidereal month.

[4] A consequence of this is that the Moon is 'dragging' on the Earth, slowing its rotation and increasing the day length by 2 milliseconds per century. The angular momentum of the system is conserved, the Moon's angular momentum increases (or, put another way, it gains rotational energy from Earth as Earth slows) and as a consequence it gradually moves further away.